Have you ever known someone who had an especially distinctive personality—someone who lit up the room or set the tone for the entire group? Perhaps this person was always acting unpredictably and you couldn’t help laughing at his antics. He was such a character!

Well, just as we appreciate people for their unique personalities, readers also appreciate characters who are portrayed so vividly that they transcend the page to invade our personal space and set the tone for our own day. Such characters invite us to become fully invested in their fates. Whether we want their evil deeds to catch up with them or we want them to be blessed beyond measure, we cannot put the book down until we learn what becomes of them.

In this post, we will explore the techniques for creating larger-than-life characters who have purpose and direction. We will craft the characters behind the life stories that we developed in our earlier post discussing character arcs. And keep in mind that everything we discuss here would apply equally well to non-human characters.

In order to bring our characters to life, we must first know them… intimately… their outer attributes, their inner attributes, their motivations and fears, their aspirations, their history and the destiny we have determined for them on their arc. We must know the role they play in the lives of the other characters and in the message of the story. We must know them, and we must be able to walk in their shoes as our pen carries them forward.

As the creator, we must know absolutely everything about each major character to be developed through the course of the story. Some details may never make their way into the story. But every detail works together to drive how the character interacts with his environment. When all of the character’s actions and mannerisms flow from a well-defined character profile, they build on each other to reinforce the reader’s impression of who the character is. Over time, the character becomes more and more real to the reader.

To start, let’s remember:

We have a message to deliver—a mission for our characters to fulfill.

We cannot pull random people off the street to fulfill our mission. We must hand-pick each character for his/her part, and then endow each character with the necessary attributes to play that part. For this, we will use two tools: the character chart and the character sheet.

Character Chart

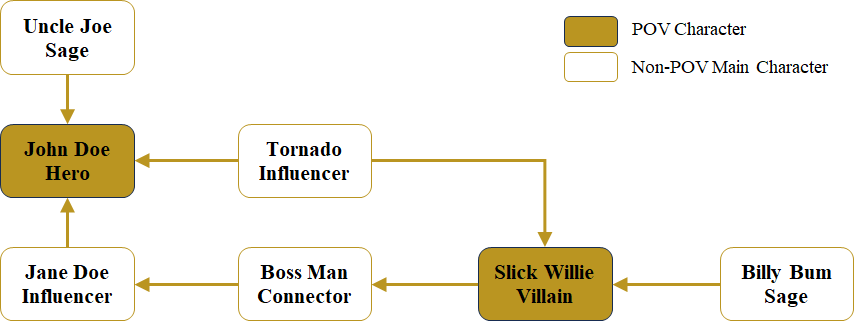

The character chart identifies the relationships between the POV characters and the non-POV main characters. The non-POV main characters play a critical role in the lives of the POV characters, but they are static throughout the story; they have no arc. The POV characters are dynamic characters that navigate the inner journey of their respective arcs.

For the POV characters to change, there must be external actors providing the impetus for that change. So, there must be at least one non-POV main character actor identified for each POV character.

In this example chart, calamity strikes in the form of a tornado. The hero’s wife is the main influence in his life, and his primary counsel comes from his uncle. His wife’s boss tries to help them by putting them in touch with Slick Willie. But Slick Willie, prodded on by advice from Billy Bum, has opted to take advantage of the calamity by scamming people out of their relief money. The hero will overcome the crisis to become the hero, and temptation and compromise will drag the villain deeper and deeper into darkness. These are the two character arcs.

NOTE: You can get creative in selecting your villain. Jerry Jenkins offers some advice on using characters or nature as the antagonist/villain.

Once the roles are laid out, it’s time to develop the attributes each character will need to fulfill their roles.

Character Sheet

The character sheet is a popular tool used by many writers to develop a comprehensive set of attributes and back story, and to help them remain consistent whenever they write about their characters in the story. Writers will typically develop their own character sheet based on personal experience. The sheet I am providing here can give you a good starting point, and will be referenced in the detailed discussions below.

As we get into some of the details of the character sheet, you may like to visit these links from Jerry Jenkins for additional pointers:

Starting with certain high-level classifications can help to automatically fill in lower level details. For example, selecting a common archetype, like Achiever, automatically tells you the character will be success-oriented, driven, and in need of praise. Selecting a specific temperament, like choleric, will automatically define emotional and psychological strengths and weaknesses. This character sheet is therefore designed to start with some of these high-level classifications and move into the lower level details.

Role

In the example character chart, I have included only three actor roles: the sage, the influencer, and the connector. But there are many potential roles you could use. Jerry Jenkins defines eight roles in his post: 8 Types of Characters to Include in Your Story.

The POV character mission is defined by how the character is meant to deliver the message of the story. The actor mission is defined by how the character is meant to propel the POV character along his arc. So, be sure to select a role suited to fulfilling that mission.

Archetype

An archetype is comprised of a stereotypical collection of personality traits commonly found together in an individual. To better understand this, you can refer to another post on Jerry Jenkins’ site: 12 Character Archetypes.

Selecting an archetype for each character can make the characters more relatable to the reader. But you don’t have to stick entirely to the traditional definitions. Even attaching one atypical attribute to a common archetype can offer tremendous potential for drama or tension in your story.

For example, what if you select the Investigator archetype, but you give your character overtones of the Peacemaker archetype as well? You will end up with someone who feels compelled to get to the bottom of every issue, someone who is adept at problem solving, but who lacks the backbone to make others execute that solution. Your character would see clearly the way the group should go, but would feel helpless to avert what he perceives to be imminent failure.

Most people don’t fit nicely into a single category. Mixing characteristics will make your characters more realistic. Just be sure to assign these attributes strategically for what each character needs to bring to the journey down the character arc. For instance, the attributes associated with the archetype frame what motivates the character to pursue or not pursue an opportunity, to take risks, etc.

Temperament

The five established temperaments are as follows: sanguine, phlegmatic, choleric, melancholy, and supine. The temperaments are closely associated with one’s personality type, although the labels used to describe the personalities depend on which test you take.

Temperament is described as the nature we’re born with while personality is described as the nature we demonstrate in response to our circumstances. For example, a natural extrovert may behave like an introvert after suffering a prolonged period of rejection. The need for social interaction would still be there, but fear would hold him back.

When creating your characters, you can play with this dichotomy to add tension and the element of surprise. If the rejection occurred in the past, the backstory will play into these temperament and personality choices you’ve made. When the story begins, the reader will get the impression that the character is really an introvert. But midway into the story, something will happen to erase the old pain and the character will suddenly become the life of the party. If you don’t reveal the backstory to the reader though, you will need to drop subtle hints along the way to indicate there may be more to your character than first meets the eye.

The Write Conversation offers guidance on how to create characters that are not always what they seem to be.

Some writers suggest taking a personality and/or temperament test on behalf of each character to help in the process of developing the characters. This will force you to think about how your characters will respond in different situations, which in turn helps you plan out your scenes to strategically execute the character arcs.

Hero’s Soul

This section is only performed for your hero, heroine, protagonist, or protector—however you are referring to your character. Heroism can be demonstrated in many different ways. What is going to cause your hero to rise to the occasion in your story? Based on this, what attributes does your hero need to possess throughout the story, and what attributes will your hero need to develop as the story progresses, so that when that critical moment arrives, he’s ready to step up and be the hero?

Now, what weaknesses or flaws must the hero overcome in order to develop those attributes? These flaws should have the potential to derail the hero’s destined act of heroism.

The Write Conversation presents some helpful insight to consider while crafting your hero:

Villain’s Soul

This section is only performed for your villain or antagonist. There are many degrees of evil, and even the most reprobate individuals usually possess some redeeming factor. What is going to make your villain turn his back on the light and commit himself to darkness? Based on this, what attributes does your villain need to possess throughout the story, and what attributes will your villain need to develop as the story progresses, so that when that critical moment arrives, he’s ready to cross the point of no return?

Now, what redeeming attributes will give your villain pause as he is contemplating whether or not to proceed with his scheme? These positive traits should have the potential to make the villain abandon his plot.

The Writer’s Digest has a couple posts that may help you set up your villain for his demise:

Supporting Cast

Iron sharpens iron! Now that you’ve identified the critical strengths and weaknesses compelling the hero and villain to journey their respective arcs, it’s time to decide what the major supporting characters are going to do to poke and prod them along their ways. Which temperaments, personalities, mannerisms, etc. would mesh or clash with your hero and villain to promote the desired change?

If your POV characters are married, the marriage itself can be treated as a character with an arc of its own. Inevitably, when one or both spouses change, the nature of their marriage changes also. And the quality of the relationship can affect both characters deeply. So, it can be helpful to fill out a character sheet for the marriage also.

If you include family members for your POV characters, they will influence the POV characters in a unique way because of their familiarity and history with each other. There should also be shared attributes and mannerisms amongst family members. Perhaps some of your hero’s weaknesses were passed down from one of his parents, which explains why he either has difficulty overcoming them or perhaps doesn’t even recognize them as an issue. Maybe your villain’s conscience is the product of his praying mother or grandmother; his final step into darkness requires that he also turns his back on them.

Sometimes your characters will more readily welcome your prod when delivered through humor and quirkiness than through a sage lecture, and the reader may welcome that bit of levity as well. But adding quirks to a character in a way that still makes the character believable can be an art. The Writer’s Digest offers 4 tips for writing a quirky character. And Reedsy provides a list of 150 useful quirks.

Backstory

The backstory plays a fundamental role in making your character who he is at the beginning of the story. You may or may not reveal any of this backstory in your book. But you will use it to lend depth to your character.

The backstory forms the personality layer over the temperament, shapes the character’s perspective, and sets triggers like landmines in the soul. It defines relationships between family members and friends. It establishes the character’s skillset through education and training. And it introduces cultural factors based on ethnicity and nationality.

Having already identified who the characters need to be in order to fulfill their respective roles in the story, the backstory determines how they came to be that way. Jerry Jenkins provides a great list of items to consider when developing the backstory.

Physical Attributes & Name

Finally, we come to the character’s physical attributes and name. Many writers start here. But if we do that, we have no foundation on which to base the characteristics we select. By first establishing the inner qualities and circumstances of the character, we are able to deliberately make the inner qualities shine through the outward demeanor.

Here are a few ideas to consider when painting your character’s portrait:

- Select a name that fits the time period, nationality and/or ethnicity.

- Invent a name that symbolizes the character’s identity or major attributes.

- Select an appropriate stature and hair, skin and eye color given the age and ethnicity.

- Select the stature and hair, skin and eye color to symbolize the character’s identity or major internal attributes.

- Include physical infirmities in accordance with events in the backstory.

- Include physical attributes that trigger some of the character flaws, like pride or insecurity.

Here are several more links with pointers on selecting the physical attributes and names:

- The Body & Identity

- The Body & Personality

- Master List of Descriptive Words for the Body

- 150 Character Mannerisms

- Believable Non-human Characters

- Creating Memorable Names

- Pitfalls When Choosing Names

- 7 Rules for Choosing Names

Alright—we’re feeding through a fire hose again. But, you now have a one-stop shop for working through the characterization exercise before you start your story. Next month, we’ll be back with an overview of plotting techniques.

Leave a comment